Making a History

The academic departments of universities have pasts, presents, and futures that are a mix of the university in which they reside and their faculty, students, and facilities. The faculty are a mix of people of various vintages with different interests ... some stay a few years and others for a professional lifetime. Students are here four years and see the department as a "present", yet their experience is a result of the past history of the department. Lastly, the buildings and facilities also reflect the past - opportunities met and overcome, stumbled into blindly, or others still unfulfilled.

This history of the Department of Biology (that began as Biological Sciences) is presented as a collection of materials based on various sources. Most important is "A History of Kansas State Teacher's College; 1903-1949" written by William Thomas Bawden and published in 1952. Others sources include the various early "announcements" (bulletins or catalogs) published by the school and recollections of current and emeritus faculty. Archival materials (including Bawden and others) of Pittsburg State University were made available by Randy Roberts, University Archivist.

- The Early Years

- Academics

- Facilities

- Chairpersons and Emeritus Faculty

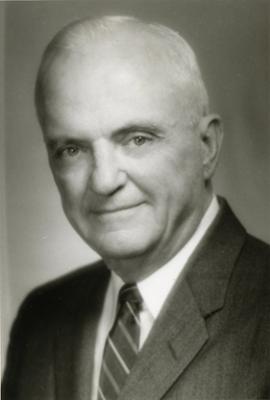

- Dr. O.P. Dellinger

The Auxiliary Manual Training Normal School opened in Pittsburg in September 1903. It later became Kansas State Teachers College of Pittsburg and then Pittsburg State University.

State normal schools prepared teachers for teaching "manual training" and "domestic science". Manual training included the industrial arts of woodworking and drafting for men. The domestic sciences for women included the design of garments, embroidery, millinery, home economics, and sewing and cooking. High school graduates came here to obtain a teaching certificate after a two-year program of instruction. Students without a high school diploma could also enroll here to finish their high school work and then continue on to obtain a teaching certificate. Later, a three-year certificate was offered.

As a part of the education of these high school students and future teachers, instruction in the sciences was needed as described here:

"The two-year curriculum offered during the opening year of the Manual Training Normal School, 1903-1904, included a ten-weeks (half-semester) course in physiology. The course was taught by Edwin Augustus Shepardson, who was employed to teach the "academic subjects," and was designated professor of mathematics and science in the announcement of the second year. The announcement for the third year, 1905-1906, named John Galatine Hall as professor of natural science and German, and described courses in botany and zoology." [Bawden, p. 171]

"Biological science was mentioned for the first time in a list of high-school units required for entrance in the announcement for 1909-1910. The description of college courses under the title, ‘Biological Science,' appeared in the announcement for the eighth year, 1910-1911, and in the faculty list, Oris Polk Dellinger, who came to the Normal School in September, 1909, was named professor of biology. The fall of 1909, therefore, may be accepted as the beginning of the Department of Biological Sciences, although it was not specifically designated a department until 1912." [Bawden, p. 171]

Dr. Dellinger went on to serve as head of the department for 30 years, from 1909 to 1939. He made many contributions to the school including serving as acting President after the death of President Brandenburg on October 29, 1940, until Rees H. Hughes became President on July 1, 1941.

Bawden described Dr. Dellinger as "an original investigator and creative thinker" who had "attracted the attention of the scientific world by the published reports of studies made by graduate students under his supervision, of studies made by scientists with whom he collaborated, and of his own investigation" and devoted a full chapter to the contributions of Dr. Dellinger (more information on Dr. Dellinger at menu link).

The early bulletins or catalogs published by the Normal School give some hint of the types of courses offered by the department and the curriculum offered. Biology did not begin as a “major” in the sense in which we use the word today – to train biologists. The school trained teachers and teachers needed to be competent in their disciplines.

According to Bawden, “majors” leading to teaching certificates first appeared in the announcement for 1912-1913. A major needed 30 hours, but two minors of 15 hours each were needed from other departments. Teachers planning on secondary education in smaller schools tried to receive wide training (not unlike today). Biological Sciences would have served either need.

The Announcement dated September 1, 1910, provides a glimpse into the very early department:

“The purpose of the courses in biology is to give to the student that knowledge of botany, zoology, physiology, and bacteriology which he needs in order to produce the best conditions of life for himself and for those depending on him. It is impossible to live effectively or to control the biological forces conditioning the existence not only of man, but of plants and animals as well, without a knowledge of biological laws.

The laboratories are well equipped to give the courses offered in biology. The equipment consists of twenty-five new compound microscopes, with one oil-immersion. Dissecting microscopes, prepared microscopic slides for histologic embryology and bacteriology, some four hundred lantern slides for demonstrations, microtomes, ovens, glassware and stain for histological studies, and incubators, sterilizers and glassware for cultural work in bacteriology.”

The early courses were listed on two levels – “Normal Secondary” courses for the high school and “Normal College” courses. The announcement for 1916-1917 listed courses under the heading, "Agriculture." In the announcement of the 1918 Summer Session, "Botany," was added as a heading. The headings were expanded to "Biology," "Physiology, Hygiene and Public Health," and "Agriculture" in the announcement for 1919-1920. The course headings "Biology," "Bacteriology," "Physiology and Hygiene" were used from the 1920-1931 announcement until the early 1950s.

The courses listed below from 1910-1913 sound very familiar to the modern ear. They are a combination of the scientific and technical with the practical.

The Sep. 1, 1910 Announcement listed the courses offered:NORMAL SECONDARY COURSE

|

The July 1912 Announcement lists the courses offered:NORMAL HIGH SCHOOL

|

The June 1913 Announcement (1913-1914) lists this course:Course 15. Eugenics. This course is designed for the domestic science student, but is open to all students of college grade. A careful review of the literature on heredity and eugenics is given, together with a study of the law of reproduction. |

Outside of Class:

Summer sessions were a part of the early University. President Brandenburg wanted to bring in “inspiring speakers and natural leaders in various lines of educational theory and practice.” In 1917, one of those speakers was Dr. C.F. Hodge, professor of biological sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon.

We are familiar today with spring break trips and summer field excursions. The year 1918 was no different when, “under the direction” of Dr. Dellinger, there was a cross-country hike and trips to the Spring River, the Farlington tree farm, the Neosho and government hatchery, and the annual trip to Noel.

Departmental Offices

Among the many campus projects during the Brandenburg presidency (1913-Oct. 1940) was a science hall that opened in 1919. It was named Carney Hall for the second governor of Kansas, Thomas Carney. Carney had served during the Civil War period, 1863-1865.

Carney Hall spread across the east side of the main campus where Yates Hall and Heckert-Wells now stand. The first two floors housed the department’s offices, classrooms, and laboratories. Also located in Carney were Chemistry, Home Economics, the Student Health Center, two social rooms, and the College Auditorium. The Auditorium had seating for 2,200, a large stage, and a pipe organ.

Concerns were raised about the structural safety of Carney Hall and measurements had shown the building was settling. As a result, Carney Hall was condemned and later razed. The department was relocated during the fall semester of 1978 (over Thanksgiving and Christmas breaks) to the basement of Dellinger and various other locations on campus for the remainder of the 1978-1979 and the 1979-1980 academic years.

An interim solution, a "science annex" building, was built on east campus and served as the main home of biology and chemistry during the 1980-1984 academic years. This building later became the home of the Wood Technology program and anchored the southeast corner of the Kansas Technology Center when the KTC was built.

Construction on Heckert-Wells Hall began soon after the razing of Carney and it was opened in fall 1984 and now houses both Biology and Chemistry (image below). James Ralph Wells was the second Chairperson of Biology and L.C. Heckert was a former chemistry professor and Chairperson of the Chemical and Physical Science Department.

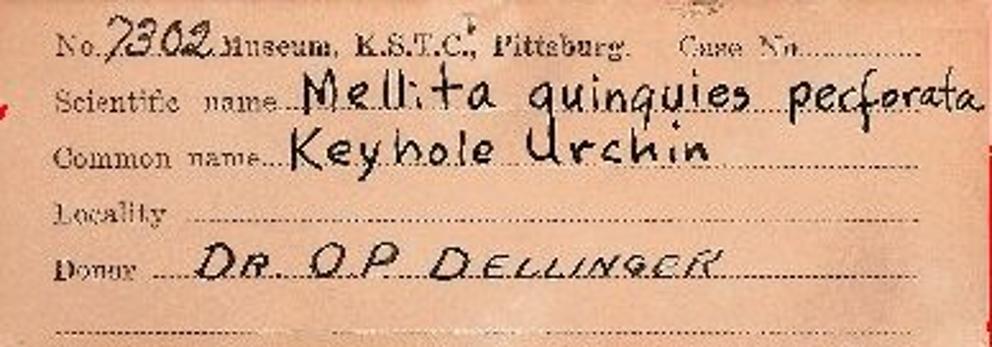

The Museum

The College Museum occupied the third floor of the Porter Hall library (completed in 1926). It consisted of two large rooms with a floor space of about 50 by 100 feet. The Announcement of 1928-1929 lists a committee responsible for the Museum. The Chairman was Dr. O. P. Dellinger, head of the Department of Biology, and the members included George E. Abernathy, George W. Trout, O. A. Hankammer, Ira G. Wilson, E. Louise Gibson, Lawrence E. Curfman.

The College Museum occupied the third floor of the Porter Hall library (completed in 1926). It consisted of two large rooms with a floor space of about 50 by 100 feet. The Announcement of 1928-1929 lists a committee responsible for the Museum. The Chairman was Dr. O. P. Dellinger, head of the Department of Biology, and the members included George E. Abernathy, George W. Trout, O. A. Hankammer, Ira G. Wilson, E. Louise Gibson, Lawrence E. Curfman.

The collections were described in the 1928-1929 Annual Catalogue as consisting of "biological, paleontological, geological, anthropological, ethnological, and historical materials." Among the collections were primitive Indian artifacts, butterflies, Indian costumes and trinkets, and other displays. The Department of Biology contributions included mounted animals, birds, reptiles, mammals, and insects. A trained museum assistant was employed. Bawden suggests it was Dr. Harry H. Hall, who came to the College on June 1, 1920, as an instructor of biology. Dr. Hall became professor of biology and was designated as Curator of the College Museum on July 1, 1942.

Over the years, the collections became dispersed or lost. When Porter Hall was remodeled in 1988, some artifacts were returned to the Department of Biology. The fossil mosasaur was saved and, some years after the move, was put on display in the third floor lobby of Heckert-Wells (image below) with some other paleontological specimens. It is probably the last piece of the biology materials intact from the old College Museum.

The Southeast Kansas Biological Field Station

Field stations serve as outdoor laboratories for teaching and research as well as for protecting natural resources.

The Southeast Kansas Biological Station includes properties managed by the Department of Biology for the purposes of research, education, and service. These sites include the Monahan Outdoor Education Center, the Natural History Reserve, the Robb Prairie, and the O'Malley Prairies. The two main properties (Monahan and Reserve) are located in the Brush Creek watershed in Crawford and Cherokee counties of southeast Kansas. The watershed - its land and water - reflects a legacy of ecological disturbance due to coal and lead/zinc mining in southeast Kansas. The properties and the surrounding area provide opportunities for understanding the restoration process and the ecology and biodiversity of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (woodland, grassland, wetlands, streams, strip-mine lakes) in the context of a human-modified landscape.

Chronology of Chairpersons

|

Dr. O.P. Dellinger |

Dr. James Ralph Wells |

Dr. J.C. "Chris" Johnson |

|

Dr. Ralph Kelting |

Dr. Dean Bishop |

Dr. James R. Triplett |

|

Dr. James Dawson |

Dr. Dixie L. Smith |

Dr. Virginia Rider |

|

Dr. Bobby Winters |

Dr. Christine Brodsky |

|

Emeritus Faculty

- Dr. James Dawson (2022)

- Dr. Joseph A. Arruda (2020)

- Dr. Cynthia S. Ford (2016)

- Dr. Steven D. Ford (2016)

- Dr. David M Gordon (2015)

- Dr. James R Triplett (2014)

- Dr. Stephen L. Timme* (2011)

- Dr. Hugh Campbell (2007)

- Dr. Leon Dinkins (2001)

- Dr. Harv Riches (2001)

- Dr. Chet Twitchell* (1999)

- Dr. Dean Bishop* (1994)

- Dr. Bette Duncan (1994)

- Dr. Ralph Kelting* (1989)

- Dr. Christopher C. Johnson* (1987)

- Dr. Leland Keller* (1987)

- Dr. Horace Hays* (1984)

- Dr. Ted Sperry* (1974 | Sperry Home website)

* deceased

William Thomas Bawden chronicles the contributions of Dr. O.P. Dellinger to Pittsburg State in Chapter 8 of A History of Kansas State Teacher’s College; 1903-1949. The chapter is repeated below, formatted for the web.

Chapter VIII- The Administration of O. P. Dellinger

THE next year, November 1, 1940, to June 30, 1941, was the period covered by the administration of Oris Polk Dellinger, as acting president; but it is to be noted that his most significant contribution to the development of Kansas State Teachers College was made during the years preceding 1940. The death of President Brandenburg, on October 29, 1940, removed a dynamic leader at a critical time when the new school year was just getting under way. For understandable reasons it was not an opportune moment for the selection of a successor. To fill so important a post it was imperative that the board of regents take time for counsel, and for deliberate and thorough consideration of policies, programs, and personalities. It was decided to appoint an acting president, and then to take whatever time might be necessary to arrive at permanent decisions.

Because of his long years of distinguished service; his familiarity with the early history, the traditions, and the accomplishments of the institution; his unmatched acquaintance among the alumni and the citizens of Kansas; his outstanding record of scholarly achievement; and his proven leadership attainments—Dr. Dellinger was the logical, unanimous, and universally accepted choice of the board for the momentous task of guiding the College through this critical period. It is appropriate at this point to examine briefly his qualifications for this assignment.

Training and Experience

First, he came to the Manual Training Normal School with a background of more than seven years of successful teaching experience in four institutions of higher learning, including two universities and a State Teachers College. A graduate of Indiana State University, he was for two years, 1901-1903, instructor of biology at the State Teachers College, Terre Haute, Indiana; four years, 1904-1908, at Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts; and one year, 1908-1909, at Winona College, Winona Lake, Indiana. During this period he served also as instructor of biology for seven summer quarters, 1902-1908, at the Biological Laboratory of Indiana State University, at Winona Lake. In addition, he spent one year, 1900-1901, at the University of Chicago, doing special work in botany under Bradley Moore Davis, a noted botanist of that day.

More significant, however, than this basis of practical teaching experience, in preparing him for the service he was to render at the Manual Training Normal School, was the prestige he had acquired, and was to augment still further with the passing of the years, as an original investigator and creative thinker in his chosen field of the biological sciences. During the years spent in research and teaching at the Biological Laboratory maintained by Indiana State University, and during the four years of graduate study and teaching at Clark University, which culminated in the award of the Ph.D. degree at the latter in June, 1907, Dr. Dellinger had attracted the attention of the scientific world by the published reports of studies made by graduate students under his supervision, of studies made by scientists with whom he collaborated, and of his own investigations.

An Authority in His Field

The two reports which probably contributed the most to focus attention upon Dr. Dellinger, and hence upon the Manual Training Normal School, to which he transferred his activities in September, 1909, were his Doctor's dissertation, which was on epoch-making study of "the structure of contractile protoplasm,"1 and the report of an earlier and related study of the vital processes of the amoeba.2

The second of these studies won the admiration and esteem of fellow scientists particularly because of certain original laboratory techniques, and unique methods of observing and recording "the events in the daily life of Amoeba proteus" one of the simplest forms of animal life, "consisting of a microscopic nucleated mass of protoplasm, perpetually changing its shape by protruding portions of its body, and nourishing itself by enveloping minute organisms and fragments of food."

By employing certain novel methods of mounting the specimens for microscopic observation, and by working in relays. Dr. Dellinger and two associates conducted the investigation "by watching continuously for six days and five nights several amoebas and keeping careful records of their activities. One amoeba was followed with special care, while several others under various conditions as to feed were also observed continuously during this period, and daily for several weeks following." In addition to photographs, and diagrammatic sketches, the report reproduced a graph of the hourly movements recorded during the six days and nights of observation, accompanied by explanatory comments on the activities noted.

Referring to the activities of search for food and the rhythm of work and rest which are basic throughout all known animal life, the authors of this study attempted to determine whether "this rhythm is necessary or is exhibited in the life of the protozoa. The answer to this question is very important in its physiological bearings." The investigation "showed very definitely that Amoeba proteus does have periods of activity and of rest as reactions connected with search for and attainment of food. These periods apparently have nothing to do with light or darkness, day or night." Without going into the details of methods or conclusions of a highly technical and involved study, it is sufficient to say that the authors were able to establish the validity of certain biological conceptions concerning which there had been serious doubts and questionings, and they dispelled certain beliefs which had been based upon insufficient evidence. "This study seems to show that the amoeba can no longer be considered as a bit of but slightly differentiated protoplasm, but must take its place in the true animal series with the rudiments at least of true animal behavior."

In due time certain conclusions of Dr. Dellinger's studies found their way into the leading and authoritative textbooks, one in England and three in the United States, and for a number of years he was the only American biologist whose findings appeared among the "classics" in the field of the biological sciences.

Prestige in the Scientific World

One of the significant factors in establishing Dr. Dellinger's place in the scientific world, and in enhancing the prestige of the Manual Training Normal School as an institution of higher learning hospitable to the concept of scientific study, research, and teaching, was his nationwide acquaintance among the leading scientists of his day. His wide acquaintance was explained in part by his contributions to the literature of his field, of which two notable examples have been cited.

But even more decisive was his extensive personal contacts, which were traceable to two sources in particular: (1) his work in the summer quarters at the Biological Laboratory of Indiana State University, where he was associated directly over considerable periods of time with other important research workers; and (2) his regular attendance for more than 30 years at the annual conferences of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Academy of Science, the Kansas Academy of Science, and other important meetings. Through these contacts he formed and maintained through the years the acquaintance of, not to say intimacy with, many of the outstanding leaders of the scientific world. As one illustrious example may be cited his close friendship with the late Hugo De Vries, 1848-1935, the eminent Dutch botanist, who was recognized as one of the immortal trio of protagonists of the theories of organic evolution.3

One practical and objective manifestation of the professional standing which the Manual Training Normal School attained as the direct result of these relationships was the inspiration imparted to students who majored in the biological sciences, and the recognition given to graduates who applied for advanced study in other institutions. Very soon after Dr. Dellinger became head of the department of biology, 1909, he began encouraging some of the more promising men and women to continue their studies elsewhere after graduation, and because of his personal connections he was instrumental in securing for them favorable consideration for appointments to fellowships and assistantships.

It is all the more remarkable that some of these appointments, and this type of recognition, antedated by several years the application by the Normal School for "approval" by the accrediting agencies, and undoubtedly the achievements of graduates and former students of the Normal School in the graduate schools of important colleges and universities were a very real factor in securing official recognition.

Not until at least ten or twelve years after biology majors began to make their mark in the eastern graduate schools did graduates of other departments of the Normal School secure similar recognition. By 1935, the number of institutions in which graduate fellowships, scholarships, and assistantships were awarded to former students of Kansas State Teachers College had grown to eighteen, and included: 4

Johns Hopkins University Brown University Washington University, St. Louis Indiana State University University of Nebraska University of Kansas University of Arkansas University of Illinois Kansas State College, Manhattan Ohio State University University of Iowa University of Minnesota University of California, Berkeley University of Wisconsin University of New Mexico Columbia University Duke University St. Louis University

Many graduates of the College, including majors from practically all departments, have gone on to distinguished achievement, and have reflected great honor upon their Alma Mater. Doctor Dellinger must be credited with a definitive part in initiating and influencing this movement. Scholarly Influence

Another circumstance worthy of note is that Doctor Dellinger was the first university-trained man to be added to the faculty of the Manual Training Normal School, and for fourteen years, 1909-1923, he was the only member of the faculty to hold the Ph. D. degree, with the exception of three persons, none of whom remained long enough to exert notable influence upon the progress and achievements of the institution: John H. Bowers, Ph. D., Associate Professor of History, 1919-1922, three years. Charles F. Lee, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology, 1909-1913, four years. George Edmund Myers, Principal, 1911-1913, two years.

In addition, two other members of the faculty held the Ped. D. degree: Jessie Craig, Ped. D., Critic Teacher, 1909-1910, one year. Frank Deerwester, Ped. D., Associate Professor of Education, 1919-1924, five years.

Because of his scholarship, leadership qualities, professional standing, and long tenure. Doctor Dellinger exercised a potent, lasting, and unsurpassed influence upon the formulation of policies, the establishment of standards, and the creation of the spirit of the school, during more than thirty years of the formative period of the institution.

The Graduate Division

One of the conspicuous contributions of Doctor Dellinger was his leadership and direction of the Graduate Division. In January, 1929, the board of regents authorized the Kansas State Teachers College of Pittsburg to confer the Master of Science degree. In April of that year, President Brandenburg appointed a Graduate Council to organize and administer the work of the Graduate Division. Doctor Dellinger was named Chairman of the Graduate Council, and served in this capacity for ten years, 1929-1939; then as Dean of the College and Graduate School for six years, 1939-1945; except for one year's leave of absence, 1933-1934, and one year as acting president, 1940-1941.

During the first of these one-year intervals. Dr. Charles Bertram Pyle served as Chairman of the Graduate Council, and during the second as Acting Dean of the College and Graduate School. Doctor Pyle was appointed professor of psychology, 1924-1927; served as head of the Department of Psychology and Educational Philosophy, 1927-1942; and professor of education and psychology, 1942-1947.

Nationwide Study

In the fall of 1933, Doctor Dellinger requested leave of absence, and devoted the year to travel, visiting colleges, universities, and teachers colleges in all sections of the United States, and making a special study of Graduate Schools, including problems of admission, qualifications of faculty personnel, curricula, costs of maintenance, organization and administration, and requirements for the higher degrees. To him must be given much of the credit for establishing and maintaining the standards of graduate study at Kansas State Teachers College, which later were found acceptable by the examining and accrediting committees of the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, and the Association of American Universities.

Dr. Dellinger's long standing friendship for Dr. Fernandus Payne, Dean of the Graduate School, Indiana State University, who inspected the College for the Association of American Universities, was an important factor in the acceptance of the institution by the accrediting agencies, through the latter's friendly counsel, advice, and practical suggestions.

Not only through his writings, and addresses at professional meetings, but personally. Dr. Dellinger was more widely known in all parts of Kansas and throughout the nation than any other member of the faculty of his day. He was among the first to carry extension courses to teachers in the communities within reach of the College, and in this way he came to know many teachers, principals, and superintendents of schools.

Personal Relationships

It is difficult to describe the vital and far-reaching influence exercised by Dr. Dellinger through his close personal relationships with members of the faculty, students, and alumni. He was always a real confidante and personal friend of hosts of students. He understood the problems of students, and contributed in many ways to their solution. He made a significant contribution to the life of the school, by participating in all student and faculty undertakings. He regularly attended as many meetings of the alumni as possible, and never failed to be called upon for the latest news from the campus.

The Critical Year

Dr. Dellinger's administration as acting president, 1940-1941, was a fitting climax to a long and fruitful association on the campus. Closer than anyone else to the problems, the policies, and the inner workings of the affairs of the College, he was able to take over the administration at a critical juncture without hesitation, uncertainty or confusion. The circumstances called for the management of a going concern, with all the details of which he was familiar, and in all departments of which he inspired confidence and good will.

The situation did not demand the inauguration of new policies or radical changes; indeed, these would have been inappropriate, if not impossible. The acting president was given a mandate to keep the institution under way, at full speed ahead, toward recognized goals, with a minimum of friction, lost motion, or unrest. All this he accomplished with consummate skill.

On July 1, 1941, Dr. Dellinger relinquished the insignia of office to the new president, Rees H. Hughes, and this narrative ends with the latter's accession.

1 O. P. Dellinger: The Cilium as a Key to the Structure of Contractile Protoplasm. A contribution from the Biological Laboratory of Clark University. The Journal of Morphology, Vol. 20, No. 2, July, 1909, pages 172-209. This study was carried on under the direct supervision of the late Dr. G. Stanley Hall, and Dr. Clifton F. Hodge.

2 David Gibbs and O. P. Dellinger; The Daily Life of Amoeba Proteus. Report of an investigation made in the Biological Laboratory of Clark University, 1905-1906. American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 19, 1908, pages 232-241

3 The others: Jean Baptiste de Lamarck, 1744-1829, French zoologist; and Charles Robert Darwin, 1809-1882, English naturalist, and author of The Origin of Species.

4 Annual Catalogue, January, 1935, page 27.